A Twitter video from Russian media company ‘Real Time’ displays footage of a harrowing refuge migration in late July of 2021.

345 ethnic Kyrgyz, with a herd of 4,000 livestock, arrive at the Tajik border after traversing rugged landscapes from their Afghan homeland.

They are a small Ismaili Shia minority from a country that is predominantly Shi’ite, their customs and beliefs are especially at risk of persecution by the Taliban.

And so only days before their region was brought under Taliban control, the group departed on a grueling journey north in an attempt to escape.

Infant mortalities were reported during the trip, and many adults became stricken with covid.

When they first arrived at the Tajik border, they were allowed entry and taken to a hospital in the Badakhshan province for treatment.

At the medical facility, they saw injured fighters, covered in blood, seeking medical help after fighting in the homeland they had just escaped.

Amidst such devastation, the Russian video unexpectedly shifts tone.

Despite efforts from the nation of Kyrgyzstan to offer the group asylum, it states that the ethnically Kyrgyz nomads headed back to Afghanistan.

A Tajik press release formally lays out the movement of the group, describing the aid services offered as temporary, and diplomatically concludes with a reaffirmation of security that – “The situation on the indicated sections of the state border of Tajikistan and Afghanistan is under the control of Tajik border guards,”

Meanwhile, the Kyrgyz government states that pleas for a safe passage and an interpreter to accompany the group across Tajikistan were never granted.

In truth, the refugees did not depart back due to hearing notions of security or a yearning for home; rather they did not have any other choice.

The predicament suggests larger foreign powers are at play –

Russia militarizes the Tajik border and has opposed accepting refugees into Central Asia.

Such an event raises the question: why was an ethnically Kyrgyz group involved in a refugee deadlock while fleeing Afghanistan?

For an explanation, let’s dive into their homeland.

A peculiar geographical region, historically at the junction of empirical conflict for centuries: the Wahkan corridor.

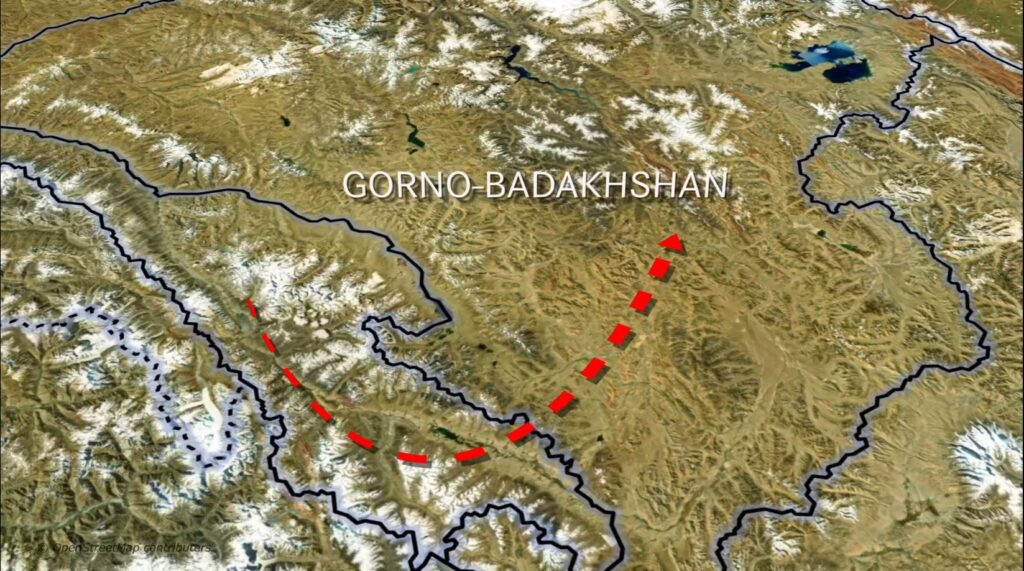

A peninsula-shaped land border – the corridor juts out 350 kilometers east out of mainland Afghanistan.

Its northern frontier is formed by the Panj and Pamir rivers, which both cut a valley split with Tajikistan.

Its southern boundary is a series of inaccessible steep peaks along the Durand Line, the border with Pakistan.

Three of Asia’s prominent mountain ranges converge here to form the Pamir Knot: the Karkakoram’s to the east, the Pamirs to the north, and the Hindu Kush to the south.

Its inhabitants are a diverse array of ethnic minorities; Farsi-speaking Pamirs, Tajiks, the aforementioned Kyrgyz, and the Wakhi, an Iranian minority who had inhabited the region for 2,500 years.

Such a fractured composition of people reflects its history as a tumultuous junction at the remote inner core of Asia.

With the Qing dynasty’s realm of control historically terminating at its Eastern edge, the area became a front line for expanding Russian and British powers in the 19th century.

The delineation of modern-day Afghanistan between these two empires became known as the Great Game.

The British feared that the Russian empire would extend southward into their possessions of India and Pakistan,

so they waged a series of wars and diplomatic strategies to blockade influence in Afghanistan.

Their first 1839 intervention failed, and became known as the ‘Disaster in Afghanistan’

It was The First Anglo-Afghan War

The Bārakzay clan became the ruling dynasty of Afghanistan, with its most powerful member, Dōst Moḥammad Khan becoming its leader

Dost was forced to balance his country between the two great powers.

The British, feeling that Dōst was either hostile to them or unable to resist Russian incursion moved to take a direct role in Afghan affairs.

But not unlike the recent war in which the United Stated Found itself in – the British while managing to take over some of the main cities could not conquer the country.

Insurrections, rebellions, and the land itself was against them. They had to pull out.

34 years later in 1873, Russian and British diplomats met to draft boundaries of their possible expansion.

Although much of the region was unexplored by their scouts, and local governments were uninvolved, it was the first semblance of Afghanistan’s modern northern boundary.

The Wakhan, hardly populated or mapped, was also added to the Afghan state. Its easternmost boundaries remained indeterminate.

Only 5 years later, Russia sent an unprompted convoy to Kabul, hoping to negotiate more land.

When the British attempted to do the same, their troops were blocked at Kyber Pass on the Afghan-Pakistan border.

They quickly launched an offensive to retaliate, which heated into the Second-Anglo Afghan war.

The British won the conflict and installed an Emir under their influence.

Although Afghanistan did not become their colonial possession, they made sure to align its foreign policy southward, conducting trade with South Asia.

Despite the British’s staked influence in the mainland of Afghanistan, the Wakhan still remained a largely unexplored frontier by European powers.

The local people easily migrated between hypothetical boundaries, unaware of the empirical chess-play encompassing their land.

Utilizing this to their advantage, the Afghan Emir stealthily occupied territory deemed Russian by agreement.

When Russian scout parties explored these distant reaches, they discovered their drafted claims were not enforced.

A British and Russian commission was sent to the area in 1895 to determine its outermost boundaries with finality.

They discovered that the immense mountain ranges enclosing the Wahkan corridor southward were impassable.

It could not be a viable route of expansion from one empire to the other.

Therefore a perfect barrier was found: a buffer between two empires unknowingly entrapping a population.

Removed from its adhered nation, and even more so from the rest of the world.

To this day the lifestyle in the region remains unchanged; pastoral and remote.

Following the Soviet invasion of 1979, it remained a cut-off safe haven from the strife of the rest of the nation.

Yet these decades of peace have come to an end. An unmarked van of Taliban fighters arrived in the Wahkan in late July of 2021.

Despite official videos and pictures of the Taliban’s arrival showing a calm takeover, an anonymous source from the Wakhan reports otherwise

“When the Taliban arrived the Afghan forces escaped to Tajikistan, and the local people hid in their homes.”

We have been in hiding for weeks. People can’t continue like this,” they said.

The supremacy of foreign powers occupies the minds of the locals.

Just as with the Great Game of the 19th century, the population is at mercy of decisions made in capitals thousands of miles away.

“People talk about the US as committing treachery against democracy because the US betrayed the Afghans to the Taliban. But All of the people think China is a big partner of the Taliban,”

the anonymous source added. They wished to remain unnamed due to fear of

persecution.

As Those who show aggression, or speak out against the Taliban are tortured.

After decades of peace in the region, the Taliban are persecuting Shi’ite minorities.

British Viceroy of India Lord Curzon once famously remarked

“We do not want to occupy it, but we also cannot afford to see it occupied by our foes.”

Such a mentality has pervaded foreign involvement in Afghanistan.

An area famously interlinked as a hotbed; home to proxy wars, internal conflicts, and international influences.

As discovered by international intel and reinforced by the anonymous source, a new global superpower is imposing its stake in that very manner.

The Wakhan corridor connects to China by the Wakjir pass. Although its lofty elevation of nearly 5,000 meters gives hint to the ruggedness of the area, it was used as a route of the Silk Road for 2,000 years.

Marco Polo was said to have crossed it on the way to China.

Jesuit priests traversed eastward, and Buddhist monks westward.

A sizeable number of British explorers, including Lord Curzon himself, navigated it to scout their colonial claims.

When Mao Zedong swept over China with communism, he sealed off entry to the pass and turned the door at the end of the corridor into a dead end.

Up to this day, there is no road, only washed-out paths navigable during the summer.

At 48 miles long, it is a peculiar land border between Afghanistan and China, separated by a 3.5 hour time difference, the largest in the world.

Recently, Chinese troops have trickled across the border for the first time in decades.

Joint Afghan- Chinese military exercises have been seen in the area.

As part of an initiative to expand mining and build infrastructure, the construction of a road has begun in the Wakhan Corridor.

The strategic importance of the pass is becoming apparent once more, and China holds it as a choke point.

In 2009, Obama approached China inquiring if the pass could be used as an entry point for US troops into Afghanistan.

China declined.

The topography of the region continues to dictate warfare.

For local populations, the effects of Chinese development could be devastating

A highway utilized by the Taliban would expedite persecution, and natural resource exploitation would destroy their nomadic lifestyle.

As is the case for many of the Chinese Belt & Road projects, the profits would not be redistributed among the local government.

The Kyrgyz of the Wakhan are no strangers to geopolitical rescrambling.

They had arrived in the Wakhan corridor fleeing the Soviets shortly after the Russian revolution.

When communist conflict encroached on their land once more during the Afghan Saur Revolution, many fled to Pakistan.

But Not all were granted refugee status.

Life at the ‘roof of the world’ is tough simply because of the elements of nature.

Wintertime temperatures reach -40.

Access to clean drinking water is sparse. Infant mortality, disease, and malnutrition are rampant.

Every time there is an alteration of a foreign power, the hardships worsen even further.

Living a tumultuous past, and braced for an uncertain future, one takeaway from the Wakhan corridor is clear: Empirical tyranny has never gone away.